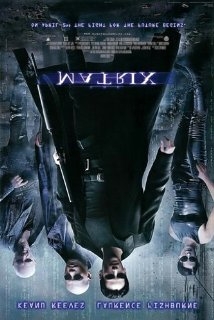

The Matrix Inverted

No one can be told what matrix inversion is. You have to see it for yourself.

Introduction

- The code for this blog post can be found in this Gist.

I find it refreshing, every now and then, to step outside of my programming comfort zone. In this post, I’m going to do that in two dimensions: language (C++) and domain (maths). On the language front, C# and Ruby are syntactically comfortable for me; F# is relatively new to me, although I do love a bit of significant whitespace. I learnt the basics of C++ in uni, but that’s about it.

A little while ago, I started writing a ray tracer in C++, for “fun”, and to learn some of the new things that were added in C++11. I didn’t get far with the ray tracer, but I did write some of the pre-requisite maths code, including a matrix inversion function. Perhaps it’s because I was doing things like writing a matrix inversion function, and not using someone else’s maths library, that I didn’t get far with the ray tracer. Anyway, let’s get this out of the way: I’m not a C++ expert. So take all this with a dose of skepticism, because I might be and probably am wrong.

I’m going to explain the matrix inversion function that I wrote, but before that I’m going to attempt to briefly explain how to do matrix inversion at a mathematical level. Again, a warning: I think I’ve got the details right, but if your Mars rover accidentally lands on Venus because you copied and pasted my matrix code, don’t blame me.

With that said, let’s jump right in. I will present an implementation of matrix inversion using C++ templates. If you’re familiar with generics in .NET, then templates are a related but separate concept: templates are compile-time-only, unlike generics, and templates are more powerful than generics in many respects; for example they support non-type template parameters and template specialisation (I’ll go into more detail on both of those below).

(Get it? Yeah, sorry about that.)

Let’s see what templates look like in C++. We’ll start by defining a matrix class:

template <int Order>

class Matrix

{

protected:

// Protected data

float m[Order * Order];

};

Note that, unlike with .NET generics, we aren’t constrained to just type parameters. The Order parameter is an integer, and we can use it at compile-time within the class definition to initialise the array, m, to the correct size.

We can declare an instance of the class like this:

auto myMatrix = Matrix<4>();

Using variadic templates, a nice feature of C++11, we can provide a constructor that takes a variable number of arguments (similar to C#’s params keyword). But this is C++. So we’re able to assert, at compile time, that the constructor has been called with the correct number of arguments:

template <int Order>

template <typename... Arguments>

Matrix<Order>::Matrix(Arguments... values)

: m { values... }

{

static_assert(sizeof...(Arguments) == Order * Order,

"Incorrect number of arguments");

}

The maths

Before we get into the matrix inversion code, let’s take a (short) journey through how matrix inversion works at a mathematical level. (I have to assume a basic understanding of matrices, because otherwise this post would be a lot longer, but there’s a nice introduction here.) According to Wikipedia, there are many ways to invert a matrix. I’m using the analytic solution, otherwise known as the adjoint method.

Why would you want to invert a matrix? Well, in 3D graphics, matrix inverses are used all the time. For example, to transform normals correctly in the presence of non-uniform scaling, you need to use the transpose of the inverse of the model matrix. Or if you have a 3D point in world space, and you want to transform it back into model space, you can transform it using the inverse of the model matrix.

The examples that follow use a 3x3 matrix, but the code we’re building will work on any square matrix.

The inverse of a matrix is analogous to the reciprocal of a number. For a number $a$, the reciprocal is $\frac{1}{a}$ (or $a^{-1}$). The original number multiplied by its reciprocal is equal to 1. Let’s say $a$ is 5:

But you can’t divide a matrix by a number - or rather you can, but it’s mathematically meaningless. Inverses are to matrices what reciprocals are to numbers. We’ll start with a 3x3 matrix, $A$:

The inverse of $A$ is a matrix $A^{-1}$ that satisfies the following equation, where $I$ is the identity matrix:

So now we need to figure out what $A^{-1}$ is. One method for doing so is the adjoint method, which involves these steps:

- Calculate the matrix of minors

- Transform that into the cofactor matrix

- Transform that into the adjoint

- Multiply that by 1 / determinant

The proof is left as an exercise for the reader.

Matrix of minors

The first step in calculating the matrix inverse is to calculate the minor of each element.

If A is a square matrix, then the minor of the entry in the i-th row and j-th column… is the determinant of the submatrix formed by deleting the i-th row and j-th column.

To calculate the minors for each element, we:

- ignore the values in the current row and column, and

- calculate the determinant of the remaining values

If you’re wondering what a determinant is, here’s what Wikipedia has to say:

In linear algebra, the determinant is a value associated with a square matrix. It can be computed from the entries of the matrix by a specific arithmetic expression, while other ways to determine its value exist as well.

Take another look at our matrix:

To calculate the minor for the top-left value (1), we calculate the determinant of the submatrix formed by deleting the first row and the first column:

Let’s apply that to all the values in the matrix:

So now we have a matrix of minors.

Cofactor matrix

The next step is to turn these minors into cofactors. Technically, the (i,j) cofactor is calculated by multiplying the minor by $(-1)^{i+j}$. More intuitively, we can apply a “checkerboard” of pluses and minuses to the matrix of minors:

We can apply this to our matrix of minors, $M$, to find the cofactor matrix, $C$:

Adjoint matrix

Next, we calculate the adjoint, or adjugate, matrix. The adjoint of $A$ is the transpose of its cofactor matrix, $C$. Transposing a matrix means swapping matrix element positions over the diagonal, with the diagonal staying the same:

Inverse matrix

Finally, the inverse matrix is the adjoint matrix multiplied by the inverse of the determinant:

If this is indeed an inverse, then multiplying the original matrix by it should result in the identity matrix. Let’s check that:

Whew - that’s enough maths for now. We’ve walked through the steps required to calculate a matrix inverse; now let’s generalise it into code.

The code

Calculating matrix minors

A minor (technically, first minor) of a matrix is the determinant of a submatrix that has a dimension one less than the matrix. So the minor of a 3x3 matrix will be the determinant of a 2x2 submatrix. So…

- first we’ll write a function -

getSubmatrix- that creates a submatrix with a dimension one less than the original matrix, - and then we’ll write another function -

calculateDeterminant- to compute the determinant of that submatrix, - and we’ll write an entry point to these two functions -

calculatorMinor.

Here’s the declaration of getSubmatrix:

template <unsigned Order>

Matrix<Order - 1> getSubmatrix(Matrix<Order> src, int row, int col)

I mentioned earlier that C++ lets us use integers as type parameters; well, it turns out we can apply mathematical operations to those type parameters, just like we can in normal code. But - and this is important - unlike generics in C#, type parameters are compiled away, so they won’t introduce any runtime overhead. In this case, the compiler will create a version of this function for each value of <Order - 1> that is actually used by our program.

Let’s see the full definition of getSubmatrix:

template <unsigned Order>

Matrix<Order - 1> getSubmatrix(Matrix<Order> src, int row, int col)

{

int colCount = 0, rowCount = 0;

Matrix<Order - 1> dest;

for (int i = 0; i < Order; i++)

{

if (i != row)

{

colCount = 0;

for (int j = 0; j < Order; j++)

{

if (j != col)

{

dest(rowCount, colCount) = src(i, j);

colCount++;

}

}

rowCount++;

}

}

return dest;

}

We pass in row and col to specify which element we want to calculate the minor for. Then we iterate through the elements in the source matrix, skipping the specified row and column, and copy the values into the output matrix.

Now that we can compute the submatrix for a given matrix element, let’s write a function to calculate the determinant of that submatrix:

template <unsigned Order>

double calculateDeterminant(Matrix<Order> mat)

{

float det = 0.0f;

for (int i = 0; i < Order; i++)

{

// Get minor of element (0, i)

float minor = calculateMinor<Order>(mat, 0, i);

// If this is an odd-numbered row, negate the value.

float factor = (i % 2 == 1) ? -1.0f : 1.0f;

det += factor * mat(0, i) * minor;

}

return det;

}

Do you notice anything strange about this code? At the beginning of this section, I mentioned that we’re first writing getSubmatrix and calculateDeterminant, and then we’ll call them from a 3rd function, calculateMinor. But we’re calling calculateMinor from inside calculateDeterminant! There’s clearly some recursion going on here.

Recursion turns out to be an elegant way of calculating a determinant. The recursive method of calculating a determinant is also known as expansion by minors. It’s easiest to think of calculateDeterminant calling calculateMinor as an implementation detail, although I’m sure that smarter brains than mine can point out the underlying connection. Recursion always requires a base case, and in this case, we’ll make a 2x2 matrix our base case - it’s easy to calculate the determinant for 2x2 matrices directly. And how do we do that? C++ allows us to specialize templates. So we can provide a “specialized” version of calculateDeterminant to use when Order equals 2:

// Template specialization for 2x2 matrix

template <>

double calculateDeterminant<2>(Matrix<2> mat)

{

return mat(0, 0) * mat(1, 1) - mat(0, 1) * mat(1, 0);

}

Finally, we can now write calculateMinor:

template <unsigned Order>

double calculateMinor(Matrix<Order> src, int row, int col)

{

auto minorSubmatrix = getSubmatrix<Order>(src, row, col);

return calculateDeterminant<Order - 1>(minorSubmatrix);

}

Calculating the matrix inverse

The maths section above described the four steps to calculate the matrix inverse:

- Calculate the matrix of minors

- Transform that into the cofactor matrix

- Transform that into the adjoint

- Multiply that by 1 / determinant

We’re now ready to implement that in code:

template <int Order>

Matrix<Order>

Matrix<Order>::invert(const Matrix<Order>& m)

{

// Calculate the inverse of the determinant of m.

float det = calculateDeterminant<Order>(m);

float inverseDet = 1.0f / det;

Matrix<Order> result;

for (int j = 0; j < Order; j++)

for (int i = 0; i < Order; i++)

{

// Get minor of element (j, i) - not (i, j) because

// this is where the transpose happens.

float minor = calculateMinor<Order>(m, j, i);

// Multiply by (−1)^{i+j}

float factor = ((i + j) % 2 == 1) ? -1.0f : 1.0f;

float cofactor = minor * factor;

result(i, j) = inverseDet * cofactor;

}

return result;

}

This function doesn’t exactly follow the four steps above. The end result is the same, but it squashes steps 2, 3 and 4 into one for loop, for efficiency.

First, we calculate the inverse of the determinant of the whole matrix; we’ll need to multiply each element of the cofactor by this value.

Then, for each element in the matrix:

- calculate the minor for the transpose of the current element (remember transposing a matrix means flipping it across its diagonal),

- calculate the cofactor (multiply the minor by $(-1)^{i+j}$),

- multiply by the inverse of the determinant, and

- place into the result matrix

And that’s it! Now we can call our invert function, and then multiply the inverse by the original and check that we get the identity matrix:

int main(int argc, const char * argv[])

{

auto original = Matrix<4>

(3.0f, 0.0f, 2.0f, -1.0f,

1.0f, 2.0f, 0.0f, -2.0f,

4.0f, 0.0f, 6.0f, -3.0f,

5.0f, 0.0f, 2.0f, 0.0f);

auto inverted = Matrix<4>::invert(original);

assert((original * inverted).approximatelyEquals(Matrix<4>::identity()));

return 0;

}

The code I’ve shown here, as well as some supporting code, can be found in this Gist.

Conclusion

I’ve shown the adjoint method of inverting a matrix inverse, implemented in C++ using templates. There are a number of improvements that could be made. One improvement would be to cache matrix minors, to avoid recalculating the same values over and over again. Also, I’m not handling singular matrices, which don’t have an inverse.

I’ve read that if you’re working with matrices larger than 4x4, then the adjoint method doesn’t scale well. For larger matrices there are apparently better choices, such as Gauss-Jordan elimination. The Laplace expansion is another option for calculating the determinant of larger matrices, but I haven’t investigated it myself.

One final caveat: you probably shouldn’t actually use this code, unless you really do need to deal with matrices of arbitrary dimension (and even then there are faster methods). In 3D graphics, for example, you know ahead of time what size of matrix you need to work with (usually Matrix3, Matrix4, and perhaps Matrix2). You’ll get better performance by hard-coding the matrix inversion functions for the sizes you need.

However, I still think it’s interesting to know how matrix inversion works, whatever you end up using in your application. Or, to put it another way:

Neo: What are you trying to tell me? That I can invert arbitrarily sized matrices?

Morpheus: No, Neo. I’m trying to tell you that when you’re ready, you won’t have to.

(With apologies to, well, everybody with a sense of humour.)