Writing a MiniC-to-MSIL compiler in F# - Part 6 - Conclusion

- This post is part of the series Writing a MiniC-to-MSIL compiler in F#.

- You can find the code for this series in the Mini-C GitHub repository.

Compiler entry point

Each blog post in this series has described one piece of the compiler pipeline. Specifically:

- Part 2 described the lexer and parser. The entry point to this code is

Parser.parse. - Part 3 described semantic analysis. The entry point is

SemanticAnalysis.analyze. - Part 4 described building the intermediate representation. The entry point is the

ILBuildertype and itsBuildClassmethod. - Part 5 described code generation. The entry point is the

CodeGeneratortype and itsGenerateTypemethod.

We can now bring all those pieces of the compiler pipeline together in the compile function, defined in Compiler.fs:

let compile (assemblyBuilder : AssemblyBuilder) code =

let assemblyName = assemblyBuilder.GetName()

let moduleBuilder = assemblyBuilder.DefineDynamicModule(assemblyName.Name, assemblyName.Name + ".exe", true)

let program = Parser.parse code

let semanticAnalysisResult = SemanticAnalysis.analyze program

let ilBuilder = new ILBuilder(semanticAnalysisResult)

let ilClass = ilBuilder.BuildClass program

let codeGenerator = new CodeGenerator(moduleBuilder, ilClass, assemblyName.Name)

let (compiledType, entryPoint) = codeGenerator.GenerateType()

assemblyBuilder.SetEntryPoint entryPoint

(compiledType, entryPoint)

This function uses a System.Reflection.Emit type we haven’t seen before: AssemblyBuilder. This is the top-level “builder” type. From it, we can create the hierarchy of modules, types, fields and methods.

The compile function isn’t used directly by calling code; instead, there are a couple of wrapper functions to compile to an in-memory assembly, or save to disk. They mainly differ in how the AssemblyBuilder object is created:

let compileToMemory assemblyName code =

let assemblyBuilder =

AppDomain.CurrentDomain.DefineDynamicAssembly(

assemblyName, AssemblyBuilderAccess.RunAndSave)

compile assemblyBuilder code

let compileToFile fileName code =

let assemblyName = new AssemblyName (Path.GetFileNameWithoutExtension fileName)

let assemblyBuilder =

AppDomain.CurrentDomain.DefineDynamicAssembly(

assemblyName, AssemblyBuilderAccess.RunAndSave,

Path.GetDirectoryName(fileName))

let (_, _) = compile assemblyBuilder code

assemblyBuilder.Save (Path.GetFileName fileName)

The unit tests mostly use compileToMemory, but a standard compiler executable (if there was one; actually there isn’t) would use compileToFile.

Tests

Talking about unit tests: I haven’t really mentioned them in this series, but there are quite a few unit tests covering several parts of the pipeline.

In addition to unit tests, there are also some integration tests that compile the code into an executable file, run the executable file, and check for the correct return value:

[<TestCase("test1.minic", Result = -5)>]

[<TestCase("test2.minic", Result = 55)>]

[<TestCase("test3.minic", Result = 3)>]

[<TestCase("test4.minic", Result = 9)>]

[<TestCase("test5.minic", Result = 127)>]

[<TestCase("test6.minic", Result = 15)>]

let ``can compile, save and execute console application with correct return value`` sourceFile =

let code = File.ReadAllText(Path.Combine("Sources", sourceFile))

let targetFileName = Path.Combine("Sources", Path.GetFileNameWithoutExtension(sourceFile) + ".exe")

Compiler.compileToFile targetFileName code

let testProcess = Process.Start(targetFileName)

testProcess.WaitForExit()

testProcess.ExitCode

Just to show that the Mini-C compiler can compile somewhat useful code, here is one of the test programs (based on one of the tests that James Van Boxtel wrote for his implementation of Mini-C):

int isqrt(int a, int guess) {

int x;

if (guess == (x = (guess + a/guess)/2))

return guess;

return isqrt(a, x);

}

int num;

float f;

void main(void) {

num = iread();

iprint(isqrt(num, num/2));

f = fread();

fprint(f * 2.0);

}

I also wrote a number of tests that check error handling works as expected:

[<TestCase("error1.minic", "MC003 A variable named 'x' is already defined in this scope")>]

[<TestCase("error2.minic", "MC003 A variable named 'y' is already defined in this scope")>]

[<TestCase("error3.minic", "MC001 Lexer error: Invalid character '^'")>]

[<TestCase("error4.minic", "MC004 Cannot convert type 'bool' to 'int'")>]

[<TestCase("error5.minic", "MC002 Parser error: Illegal token [a-zA-Z_][a-zA-Z_0-9]*. Expected \+,-,\*,\(,\),\[,\],;,,,%,/,=,\|\|,==,!=,<=,<,>=,>,&&,\.")>]

[<TestCase("error6.minic", "MC005 Operator '<' cannot be applied to operands of type 'bool' and 'int'")>]

[<TestCase("error9.minic", "MC006 The name 'foo' does not exist in the current context")>]

[<TestCase("error10.minic", "MC004 Cannot convert type 'bool' to 'void'")>]

[<TestCase("error11.minic", "MC007 Call to function 'test' has some invalid arguments. Argument 1: Cannot convert from 'int' to 'bool'")>]

[<TestCase("error12.minic", "MC008 Function 'test' takes 1 arguments, but here was given 2")>]

[<TestCase("error13.minic", "MC006 The name 'foo' does not exist in the current context")>]

[<TestCase("error14.minic", "MC009 No enclosing loop out of which to break")>]

[<TestCase("error15.minic", "MC004 Cannot convert type 'void' to 'int'")>]

[<TestCase("error22.minic", "MC010 Cannot apply indexing with [] to an expression of type 'int'")>]

[<TestCase("error23.minic", "MC004 Cannot convert type 'int[]' to 'int'")>]

[<TestCase("error24.minic", "MC011 A function named 'func' is already defined")>]

[<TestCase("error25.minic", "MC012 Program does not contain a 'main' method suitable for an entry point")>]

let ``can detect semantic errors`` sourceFile (compilerError : string) =

let code = File.ReadAllText(Path.Combine("Sources", sourceFile))

Assert.That(

(fun () -> Compiler.compileToMemory (AssemblyName(Path.GetFileNameWithoutExtension sourceFile)) code |> ignore),

Throws.TypeOf<CompilerException>().With.Message.EqualTo compilerError)

This is one of the areas that, in my opinion, I got right: in most cases I wrote the tests first, and then implemented the required functionality. This approximately-TDD way of working is great for writing compiler code, where the inputs and outputs are often very clear and can be tested easily. (Obviously, I’m speaking from the experience of writing Mini-C; everything gets more complicated in a real language.)

GUI

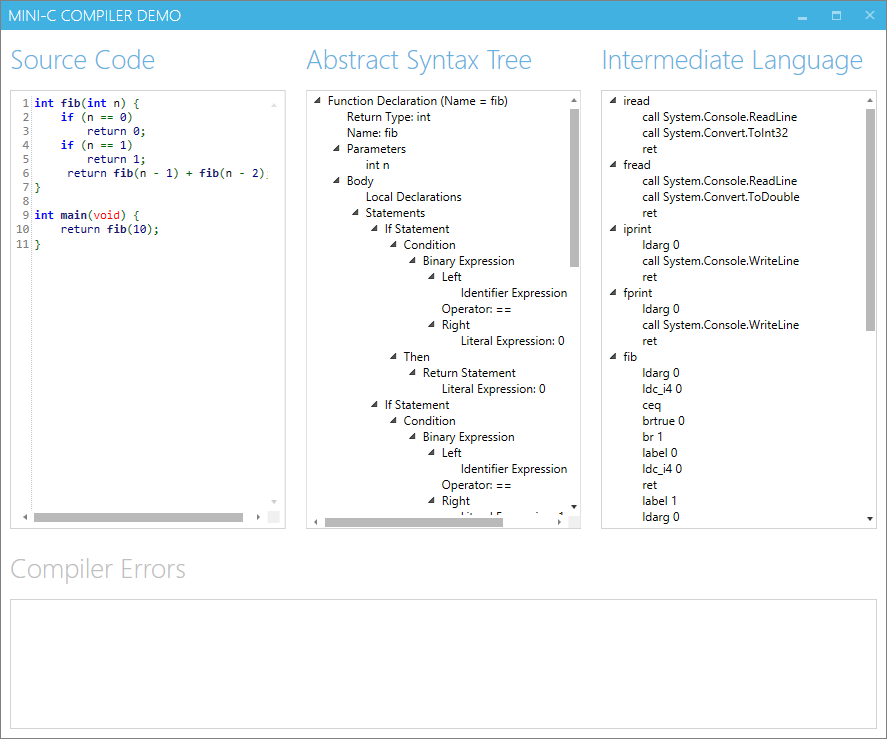

Towards the end of the project, I added a GUI to showcase the most interesting parts of the compiler pipeline:

If you’ve followed along this far, I encourage you to download the code and try out the GUI by running the MiniC.Compiler.Demo application.

As you change the source code on the left, the Abstract Syntax Tree and Intermediate Language panels update in real-time.

Post-mortem

If I was starting this project now, I would do some things differently.

-

I wouldn’t use the Piglet lexing and parsing library. It’s an elegant library, but it’s really designed for C#. Instead, I would use FParsec. Philip Trelford has a nice write-up about using FParsec to parse C#.

-

I would use modules and functions more, and types and methods less. For example, I have a

CodeGeneratortype with a single public method,GenerateType. It would be more idiomatic, and I think more elegant, to simply have agenerateTypefunction in aCodeGeneratormodule. There are certainly times when writing F# code where full-blown types make sense, but I can’t think of many in the Mini-C source code. The fact that I used them at all probably betrays my C# background, even though I was trying my best to write idiomatic F# code. -

I would extend the language and compiler to support calling into other .NET assemblies - that would be an interesting addition, and is obviously an important step towards making a real language.

-

I wouldn’t wait so long to write about it!

And that about wraps things up. I’ve been writing this series (on and, admittedly, mostly off) since April. Thank you for reading this far. I hope it has been interesting, and perhaps even inspired some of you to write your own compilers, toy or otherwise! The more interesting language design concepts there are out there, the better for all of us.