DryRunner: Isolated integration testing for ASP.NET

TL/DR

DryRunner is an open source library for .NET that enables isolated integration testing for ASP.NET websites.

The problem

ASP.NET might not have such a rich ecosystem of testing frameworks as, say, Ruby on Rails, but the situation is improving. Tools like SpecFlow, a .NET port of Cucumber, make integration testing much easier than it used to be. I like SpecFlow a lot. It’s a great way to do end-to-end testing of an ASP.NET website. Combined with a browser automation tool like Selenium, it lets you programmatically simulate a user clicking around in a real web browser, performing a sequence of steps - perhaps creating an account or logging in.

The trouble is: on which instance of your site should you run these tests? If the test involves creating an account, for example, then you don’t want to clutter your production database with all those test accounts. You probably also don’t want to use your local development site - the one running in IIS or IIS Express on your own computer - partly to avoid clutter, and partly so that you can treat test data as disposable, in case you want to empty the database before a test run.

I imagine a common solution is to have a test instance of the site running on a server somewhere, perhaps in combination with a continuous integration server like TeamCity. TeamCity could grab the latest code, deploy it to the test instance, empty the test database, and run the SpecFlow tests against the test instance.

Which is all well and good - and it is good - but what if you want to run this type of test on your own computer, before checking in? Testing is supposed to be all about a quick feedback loop, after all.

Introducing DryRunner

I couldn’t find an existing solution that I was happy with, so I wrote DryRunner. DryRunner allows you to do isolated integration testing for ASP.NET websites - and by isolated, I mean that the test website is separate, uses its own database, exists in a separate folder structure, and can be deleted when you’ve finished with it.

DryRunner itself is actually quite simple, because it’s built on a few existing Lego blocks: ASP.NET deployment packages, web.config transforms, and IIS Express.

So what does DryRunner actually do? It will:

- deploy a test version of your website to a temporary location,

- host the test version of your website using IIS Express, and

- clean up afterwards by deleting the test version.

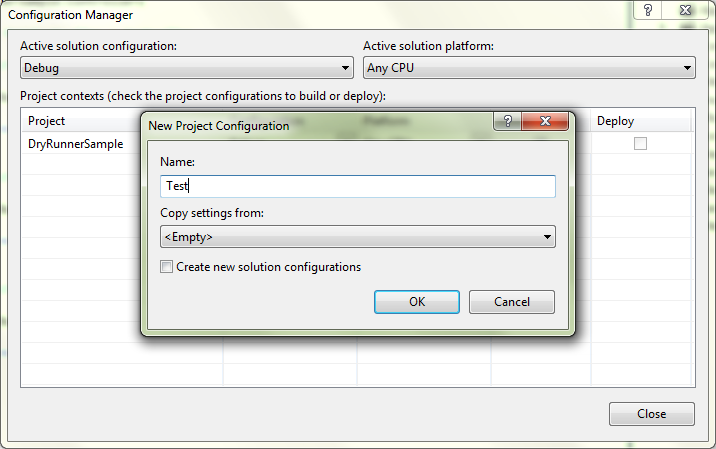

DryRunner requires you to create a Test build configuration (alongside the usual Debug, Release and any other build configurations you may already have). You can use Web.Test.config to configure test-specific database connection strings, and other test-specific settings.

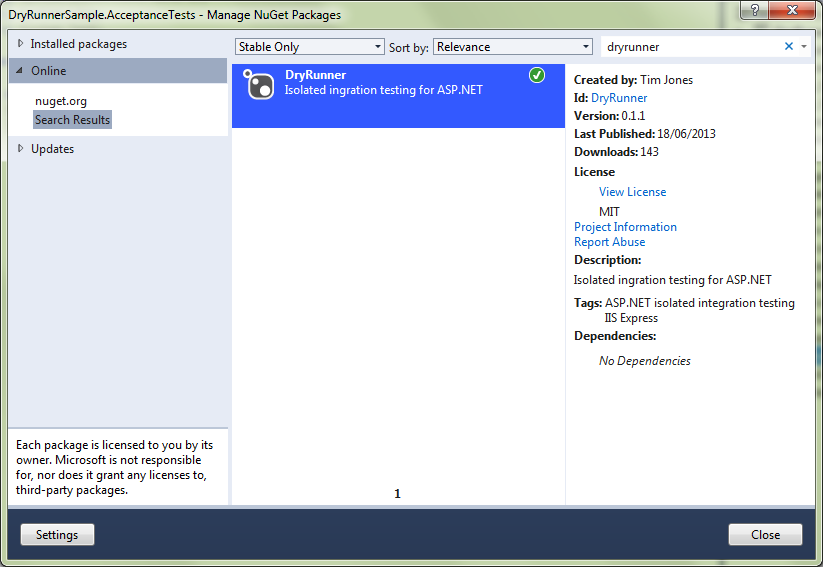

DryRunner is open source, and you’ll find the source code on GitHub. More usefully, there’s a DryRunner package on NuGet.

For example…

I think a concrete example will help more than an abstract explanation would, so here goes. (For more concise usage instructions, see the GitHub page.)

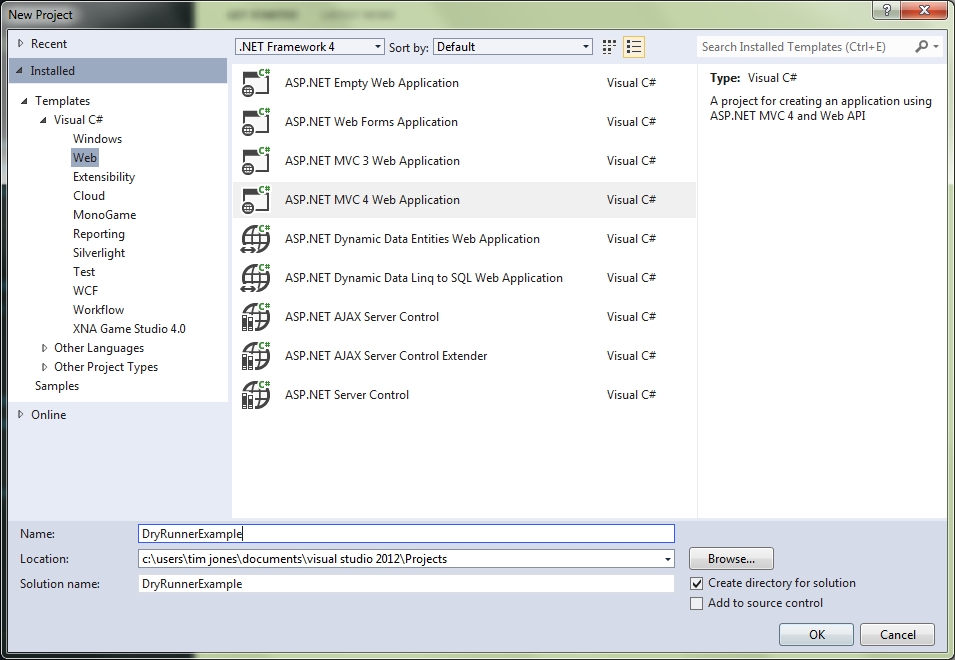

First, we’ll create a new ASP.NET MVC 4 Web Application.

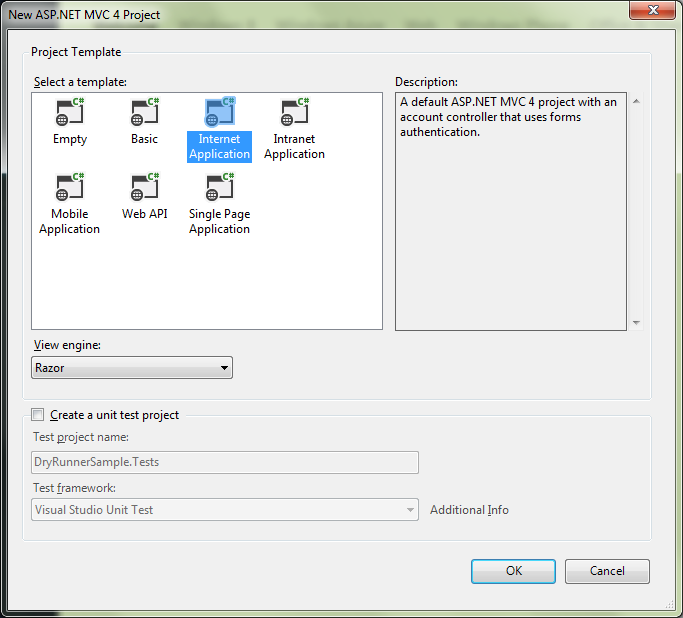

Choose the Internet Application template, and don’t create a unit test project. We’ll create one ourselves later.

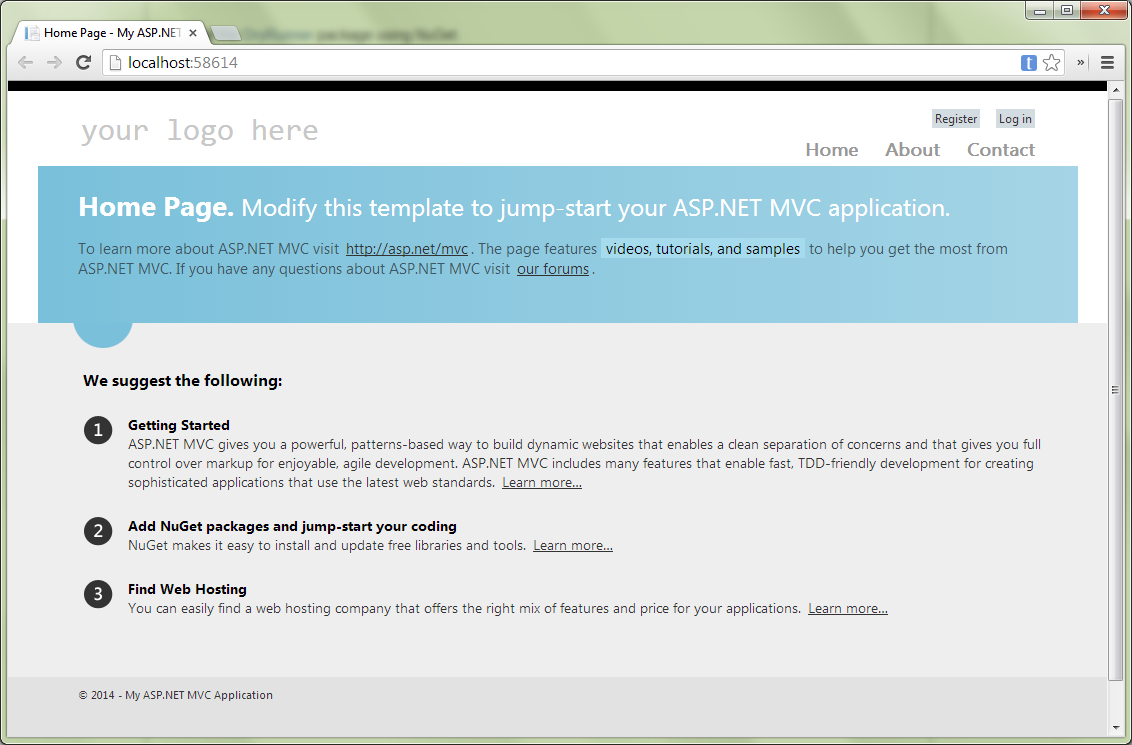

If we start the website now, we’ll see this in the browser. Later on, we’ll write an integration test that ensures the phrase “To learn more” is present on the page.

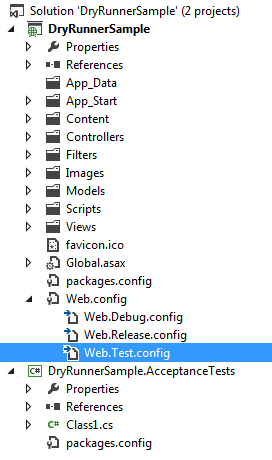

Before using DryRunner, we need to create a Test configuration for the website you want to test. DryRunner will build the website using the Test configuration, including the relevant web.config transform, if you have one. Right-click on the solution name in Solution Explorer, and click “Configuration Manager…”. Find your web project, and in the Configuration column, choose “

Now add a new Class Library project named [ProjectName].AcceptanceTests. Install the NUnit and DryRunner NuGet packages (skip NUnit if you prefer MSTest or another test framework):

Add a test class named HomePageTests.cs to the test project:

using System.Net;

using DryRunner;

using NUnit.Framework;

namespace DryRunnerSample.AcceptanceTests

{

[TestFixture]

public class HomePageTests

{

private const int Port = 9000;

private TestSiteManager _testSiteManager;

[SetUp]

public void SetUp()

{

const string websiteProjectName = "DryRunnerSample";

_testSiteManager = new TestSiteManager(websiteProjectName, Port);

_testSiteManager.Start();

}

[TearDown]

public void TearDown()

{

_testSiteManager.Stop();

}

[Test]

public void HomePageContainsCorrectContent()

{

using (var webClient = new WebClient())

{

string html = webClient.DownloadString("http://localhost:" + Port);

Assert.That(html, Contains.Substring("To learn more"));

}

}

}

}

I’d normally use frameworks like SpecFlow and Selenium to avoid matching against the raw HTML, but I wanted to keep this example simple.

Run this test - it should pass. And that’s pretty much it - we’re now able to run integration tests against an isolated copy of an ASP.NET website.

So far, there’s not really any benefit over running integration tests in-place on your development website. But you will almost certainly want to manipulate a database as part of your tests. Here’s where DryRunner comes into its own: it let you use test-specific settings, such as a test-specific database connection string. This is best done using web.config transforms. In your web project, right-click on Web.config, and choose Add Config Transform. You’ll see a Web.Test.config file is added to the project. Refer to the web.config transformation syntax to see how you can insert new settings or replace settings inherited from the base Web.config.

Give it a try

I hope someone out there finds this useful. I know of DryRunner being successfully used in some ASP.NET shops already, and if you use it I’d love to hear from you, particularly if you have any suggestions for improvement.